LLVM-CFI and the Linux Kernel (CFI 1/4)

This blog series explores the usage of Control-Flow Integrity (CFI) in the Linux kernel, with a specific focus on data-only attacks. While CFI is a powerful mitigation that restricts control-flow hijacking, it does not protect program data, which can still be targeted by attackers. The series will analyze a set of real-world Linux kernel bugs/vulnerabilities and demonstrate how each of them can be exploited using data-only techniques, without violating control-flow integrity.

These posts are adapted from my Master thesis, which explored the effectiveness of Control-Flow Integrity (CFI) on a large set of bugs collected by Syzbot.

Overview

- LLVM-CFI and the Linux Kernel (this post)

- From Crash Report to Root Access: Building an End-to-End Data-Only Exploit

- Revisiting CVE-2017-7308

- Revisiting CVE-2017-11176

What is CFI?

Control-Flow Integrity (CFI) is a mitigation designed to limit what an attacker can do after gaining control over execution. The idea is to restrict the program’s execution to follow a precomputed control-flow graph (CFG), typically built using static analysis. If an attacker corrupts a pointer or a return address, they should still be constrained within this graph.

CFI focuses on two kinds of control transfers:

- Forward edges: indirect calls, jumps via function pointers, etc.

- Backward edges: return instructions that jump to the saved return address

One of the earliest and most influential CFI designs came from Abadi et al., presented in Control-Flow Integrity: Principles, Implementations, and Applications. Their system allowed indirect jumps only to known function entry points and introduced a shadow call stack to handle backward edges, storing return addresses in a separate memory region not accessible to attackers.

Their model assumes a strong adversary: full control over all writable memory, but not the code itself.

Subsequent work has proposed improvements focused on:

- CFG precision

- Performance overhead

- Compatibility with large and complex codebases

An ideal design would enforce a perfect CFG, add negligible overhead, and require minimal integration effort. In practice, designs make compromises depending on the target use case. This complexity is discussed in works like Control-Flow Integrity: Precision, Security, and Performance and CONFIRM, which evaluate real-world deployment and performance trade-offs.

LLVM-CFI in the Linux Kernel

CFI support has extended from user-space to operating systems like Linux. This introduces specific constraints: for example, due to interrupt handling and control paths unique to the kernel.

In Linux, CFI is implemented using LLVM-CFI, part of the Clang compiler. It includes protections for both forward and backward edges.

Backward Edges: ShadowCallStack

On ARM, the r18 register is used to store the base address of a shadow call stack. This pointer is never written to the main stack, preventing attackers from locating or tampering with it via stack corruption.

Forward Edges: Function Classes and Jump Tables

LLVM-CFI groups functions into classes based on their prototypes (i.e., return type and argument types). Each function class has an associated jump table containing valid function targets.

Indirect calls are rewritten so that:

- Function pointers reference entries in a jump table.

- A bounds check verifies the target is within the expected jump table.

- If the check fails, the kernel crashes.

Here is an example check the compiler could add (in C-style pseudocode):

int action1 (int arg1);

int action2 (int arg1);

double action3 (int arg1);

void demo(int arg) {

int (*f) (int);

(...)

if (JT0_BEGIN_ADDR <= f && f < JT0_END_ADDR)

f(arg);

else

panic();

}

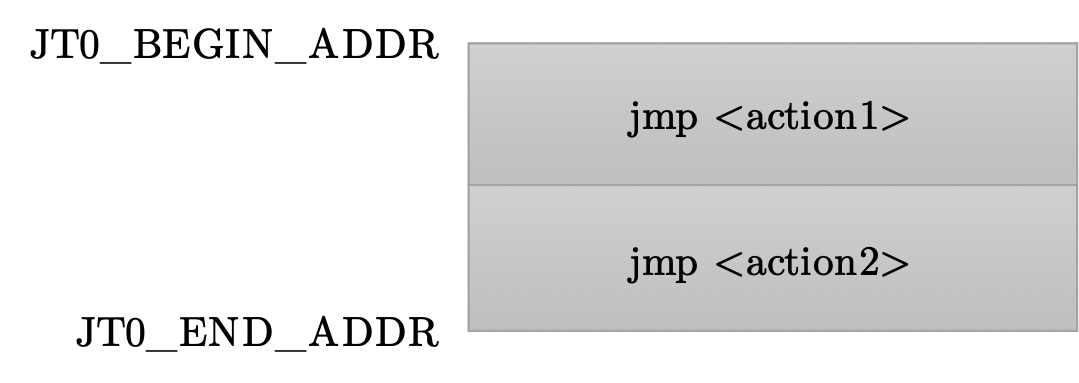

and the jump table for the int (*)(int) functions:

In this example, even if f is corrupted, it can only point to action1 or action2. Jumping to any other address results in a panic.

Function prototypes that are too generic (like void (*)(void)) result in large classes, which increases the number of valid targets per indirect call. In the Android kernel:

- Around 80% of indirect call sites are restricted to fewer than 20 valid targets

- About 7% allow more than 100

Although techniques like Control-Flow Bending demonstrate that attackers can operate within the CFG, in the following posts, we will assume an ideal CFI model that fully enforces control-flow integrity and we investigate what kinds of attacks remain possible under this assumption.

While CFI has not yet been upstreamed into mainline Linux, it is already deployed in production systems. For instance, Android has enabled it by default since the Pixel 3. Most of the components required for upstream support have already landed.

Data-Only Attacks

CFI only protects control-flow data. All other program state, including local variables, flags, and data pointers, remains vulnerable.

Example:

void spawn_privileged_shell(void) {

int is_admin = 0;

char username[32];

char password[32];

scanf("%s:%s", &username, &password);

(...) // Perform permission checks and maybe set is_admin

if (is_admin)

execve("/bin/sh", NULL, NULL);

}

If scanf writes beyond the bounds of username, it can overwrite is_admin. The control flow is unchanged, but the attacker can escalate privileges by modifying data.

In kernel space, this issue becomes more critical due to the presence of sensitive data such as credentials and page tables. For example, PT-Rand demonstrated how attackers could mark kernel code as writable by tampering with page table entries, then disable CFI entirely by patching the checks.

Protecting a single structure is not enough. One of the attacks discussed in this series involves scanning memory for the cred structure of the current process and modifying it to simulate calls to prepare_kernel_cred and commit_creds. This results in privilege escalation, even without control-flow hijack.

Defenses like PrivGuard attempt to identify and protect sensitive kernel structures such as credentials. But there’s no guarantee that every critical data structure has been identified. Broader protections like data-flow integrity exist, but current implementations are too expensive to be practical in the kernel.

In the next parts of this series, we’ll go through three concrete examples of Linux kernel vulnerabilities, including one recent bug discovered with Syzkaller, and show how they can be exploited using data-only attacks, even with CFI enabled.